Module Overview

Hello and welcome to this course on ways to reduce unwanted, problematic, or even dangerous behavior, or to increase a desirable behavior. Before we dive into this most interesting area, it is important to make sure we all are on the same sheet of music. We will revisit what psychology and learning are, and how changing behavior fits into our field. As it is always important to understand where you came from, we will discuss several of the pioneers in the field of learning who are associated with the school of thought called Behaviorism. Behavior will then be defined, its dimensions discussed, and the field of applied behavior analysis will be described to include pertinent information any applied behavior analyst will need to gather. To round out the module, we will discuss how learning is shared with the broader scientific community.

Module Outline

Module Learning Outcomes

Section Learning Objectives

To start things off, let’s take a step back in time. Behavior modification is an area under the field of psychology. Think back to when you took your introduction to psychology course. How did the text, and your professor, define psychology? If you cannot remember, how would you define psychology now that you have likely taken several psychology courses? After giving this some thought, look at the official definition.

Psychology is the scientific study of behavior and mental processes.

Let’s examine this definition before we go on.

For the student taking a class in behavior modification, we might say that we seek to study behavior (scientifically of course), but in terms of ways to change it for the betterment of not only the person, but all around him or her. We will spend a lot of time examining behavior in this way but do note that we will touch on cognitive processes because at times, it is not a specific action that we need to change, but the way we think about it. For instance, you might want to reduce procrastination, eliminate unnecessary anxiety, change a maladaptive cognition, or reverse a particularly bothersome habit. More on this later in the book.

So our discussion focuses on the scientific study of behavior and specifically the cognitive process of learning. What is learning then?

Learning is any relatively permanent change in behavior due to experience and practice.

Learning is key to any study of behavior modification. In fact, as you will see shortly, it is based on the model of learning developed by B.F. Skinner about 90 years ago and going back over 100 years if you consider the work of John B. Watson. If we make an undesirable behavior, we continue doing so because it in some way produces favorable consequences for us. We have learned to associate the behavior with a reinforcer. Let’s say we wake up in the morning and instead of going to the gym, we get on our phone. Of course, getting exercise is beneficial in many ways, but we choose to surf the internet, play a game, respond on Facebook, or make a tweet instead. Why? We enjoy doing so and love it when people like our posts. The undesirable behavior is using our phone and the consequences are the enjoyment we feel and our contributions being liked or shared by others. These consequences reinforce the undesirable behavior.

Fortunately, learning is only a relatively permanent change in behavior. Nothing is set in stone and what is learned can be unlearned. Consider a fear for instance. Maybe a young baby enjoys playing with a rat, but each time the rat is present a loud sound occurs. The sound is frightening for the child and after several instances of the sound and rat being paired, the child comes to expect a loud sound at the sight of the rat, and cries. This is because an association has been realized, stored in long term memory, and retrieved to working memory when a rat is in view. Memory plays an important role in the learning process and is defined as the ability to retain and retrieve information. The memory of the loud sound has been retained and retrieved in the future when the rat is present. But memories change. With time, and new learning, the child can come to see rats in a positive light and replace the existing scary memory with a pleasant one. This will affect future interactions with rats.

In some cases, we adjust our behavior based on feedback we receive from others. Joking around with our significant other after they had a long and hard day at work will be perceived differently than a day in which they received an exemplary performance evaluation and a raise. Or the feedback may come from ourselves, such that we stop working out because we notice our heartrate has reached dangerous levels or we turn off the television because we are distracted. Our ability to carefully consider our actions and the effect they have on others or ourselves, and to make such adjustments, is called self-regulation. We self-regulate or self-direct more than just our actions. We can also control our thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and impulses. You might think of self-regulation as a form of behavior modification but in the short term. It could be long term too. To lose weight, we need to exercise on a regular basis, watch what we eat, manage our stress, and get enough sleep. A few days of doing this will not produce the results we seek. We need to stay committed for many months or even years.

This leads to the topic of self-control and avoiding temptations. It takes a great deal of willpower to not sleep in, get fast food for dinner, stay up late watching Netflix, or let demands in our environment overwhelm us. This is sometimes called brute self-control (Cervone, Mor, Orom, Shadel, & Scott, 2011) and if it goes on for too long it can leave us in a weakened state and cause us to give in to our desires (McGonigal, 2011). More on this later.

Section Learning Objectives

Psychology’s past has included several major schools of thought, or a group of people who share the same general theoretical underpinning, use similar research methods, and address most of the same questions. Historically, these schools have included structuralism, functionalism, psychoanalysis, Gestalt psychology, humanistic psychology, positive psychology, cognitive psychology, and evolutionary psychology. Behaviorism, as the ninth, is the school of thought that was dominant from 1913 to 1990 before being absorbed into mainstream psychology. Behaviorism focused on the prediction and control of behavior. It went through three major stages – behaviorism proper under Watson, lasting from 1913-1930; neobehaviorism under Skinner, lasting from 1930-1960; and sociobehaviorism under Bandura and Rotter, lasting from 1960-1990. Before we dive into these stages let’s briefly discuss two influential figures who affected the earliest stages of behaviorism. Then we will discuss each stage and its key figures who have contributed to behavior modification as it exists today.

1.2.1. Antecedent Influences

Ivan P. Pavlov (1849-1936). In 1904, Pavlov received the Nobel Prize for his research on digestion, but for the field of psychology, he is noteworthy for his discovery of conditioned reflexes (Pavlov, 1927), or reflexes that are dependent on the formation of an association between stimulus and response. Of course, you likely know of Pavlov’s dogs and how he stumbled upon this discovery haphazardly. He noticed that the dogs would begin salivating before the food was placed in their mouth. They did so at the sound of a bell ringing, sight of the food, or upon hearing footsteps in the hallway. They made a connection between these neutral stimuli and getting food, which led to the salivation response. More on this in Module 6.

Edward Lee Thorndike (1874-1949). Influential on the development of Skinner’s operant conditioning, Thorndike proposed the law of effect (Thorndike, 1905) or the idea that if our behavior produces a favorable consequence, in the future when the same stimulus is present, we will be more likely to make the response again, expecting the same favorable consequence. Likewise, if our action leads to dissatisfaction, then we will not repeat the same behavior in the future. He developed the law of effect thanks to his work with the Puzzle Box. Cats were food deprived the night before the experimental procedure was to occur. The next morning, they were placed in the puzzle box and a small amount of food was placed outside the box. The cat could smell the food, but not reach it. To get out, a series of switches, buttons, levers, etc. had to be manipulated and once done, the cat could escape the box and eat some of the food. But just some. The cat was then promptly placed back in the box to figure out how to get out again, the food being its reward for doing so. With each subsequent escape and re-insertion into the box, the cat became faster until he/she knew exactly what had to be done to escape. This is called trial and error learning or making a response repeatedly if it leads to success. Thorndike also said that stimulus and responses were connected by the organism which leads to learning. This approach to learning was called connectionism.

1.2.2. Stage 1: Behaviorism Proper (1913-1930)

John B. Watson. Behaviorism began as a school of thought in 1913 with the publication of “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It” in Psychological Review (Watson, 1913). It was Watson’s belief that the subject matter of psychology was to be observable behavior. He is most famous for his Little Albert experiment in which he and his graduate student, Rosalie Rayner, conditioned Albert to be afraid of a white rat by pairing the sight of the animal with hearing a loud sound. This was described earlier in the discussion of learning being relatively permanent and will be covered in more detail in Module 6 when we discuss respondent conditioning. Watson also described three unlearned emotional response patterns inherent in all people (fear, rage, and love). All other emotions arise from these basic emotions via conditioning and so are called conditioned emotional responses.

What is maybe most fascinating about Watson’s influence is that he was able to change how psychologists studied human beings. Instead of a study of behavior and mental processes, Watson shaped psychology to be simply a study of behavior, and its prediction and control. This shift began in 1913 and would remain this way for almost five decades. This is not to say that all psychologists renounced cognitive studies. The Gestalt psychologists kept the flame of cognitive processes at least somewhat going; a flicker at best. It is beyond the scope of this class, but if you take a class in the history of psychology you will quickly discover that why Watson was able to do this was not rooted in psychology or even science, but within the discipline of philosophy and the worldview of mechanism.

1.2.3. Stage 2: Neobehaviorism (1930-1960)

B.F. Skinner (1904-1990). Skinner developed operant conditioning, discussed schedules of reinforcement, and the process of shaping by successive approximations (Skinner, 1953). His work was the foundation for behavior modification (Skinner, 1938) and will be covered in detail throughout this textbook.

Edward Chance Tolman (1886-1959). Tolman proposed the idea of purposive behaviorism or goal-directed behavior (Tolman, 1932) such as a rat navigating a maze with the intent to make it to the goal box where water is at, or a cat trying to escape Thorndike’s puzzle box to obtain nourishment. He also proposed the idea of cognitive maps, proposed a cognitive explanation for behavior, described intervening variables or unobserved factors that are the actual cause of behavior, and rejected Thorndike’s law of effect. These accomplishments make him a forerunner of contemporary cognitive psychology.

1.2.4. Stage 3: Sociobehaviorism (1960-1990)

The timing of the development of sociobehaviorism is rather interesting. Coming almost 50 years after the start of behaviorism, it rose and flourished during the cognitive revolution in psychology. Lead by Julian Rotter, famous for the concept of locus of control, and Albert Bandura, discussed below, the sociobehaviorists rejected Skinner’s dismissal of cognitive processes and proposed a social learning theory. The third stage of behaviorism occurred at the same time that humanistic and cognitive psychology reshaped how psychologists studied people and brought back the study of the mind.

Albert Bandura (1925-2021). Bandura is most well-known for his Bobo Doll experiment and the social cognitive theory. He criticized Skinner for not using human beings in his experiments and for focusing on single subjects and mostly rats and pigeons. Since people do not live in social isolation, we must not ignore these social interactions. His approach allowed for the modification of behaviors society saw as abnormal. His brand of behavior modification focused on the fact that people model or learn by observing others. As we learn undesirable behaviors in this way, we can unlearn them as well. More on this in Module 6. He also proposed the concept of self-efficacy which we will discuss in Module 3 (Bandura, 1982) and vicarious reinforcement, or the idea that we can learn by observing others and seeing what the consequences of their actions are.

1.2.5. Final Thoughts

We will discuss respondent conditioning (Pavlov and Watson), operant conditioning (Skinner and Tolman), and social learning theory/observational learning (Bandura and Rotter) throughout this course, and how the various procedures each learning model has developed can be used to modify human behavior. For now, simply recognize that these models are all related and built off of each other.

Section Learning Objectives

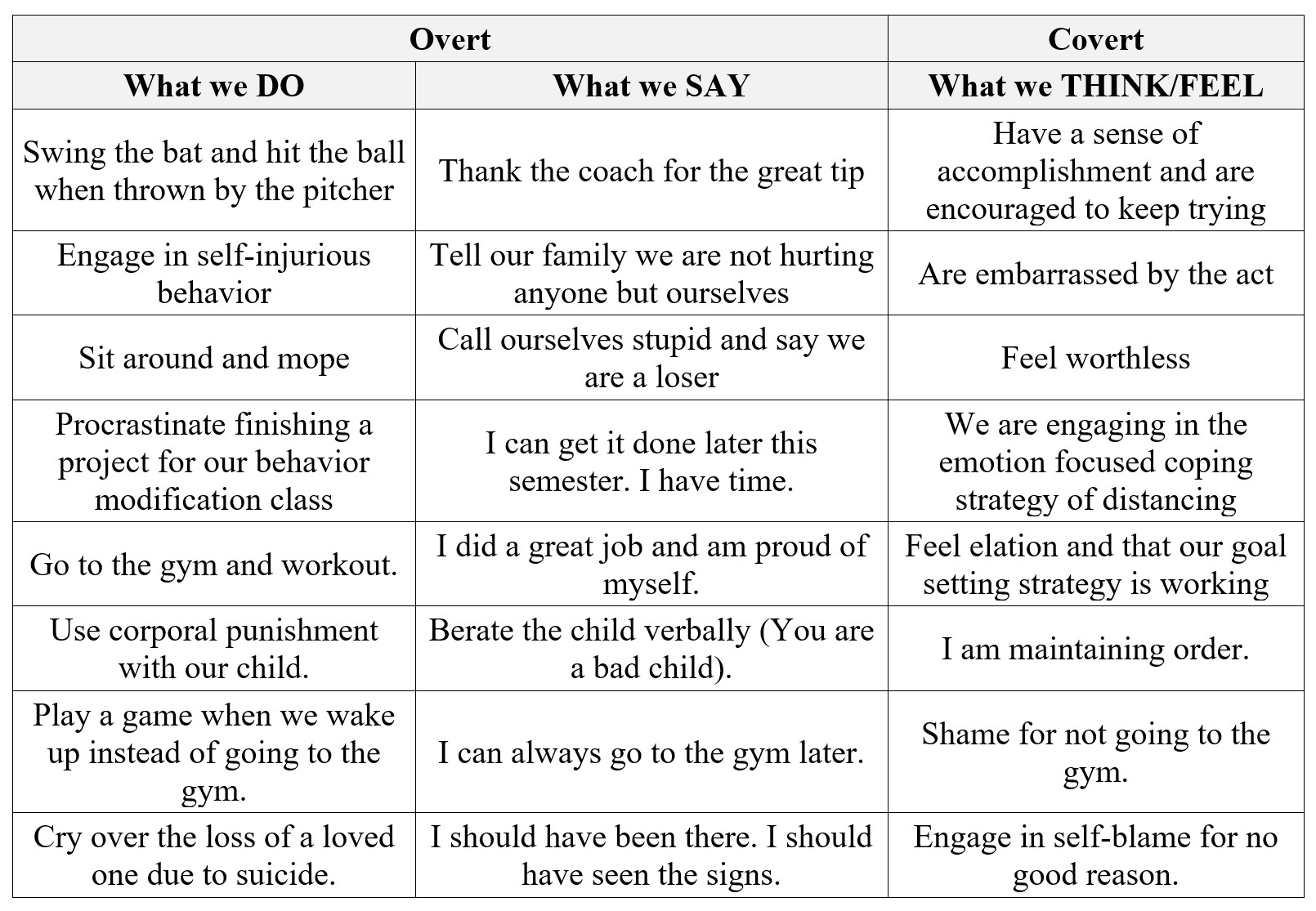

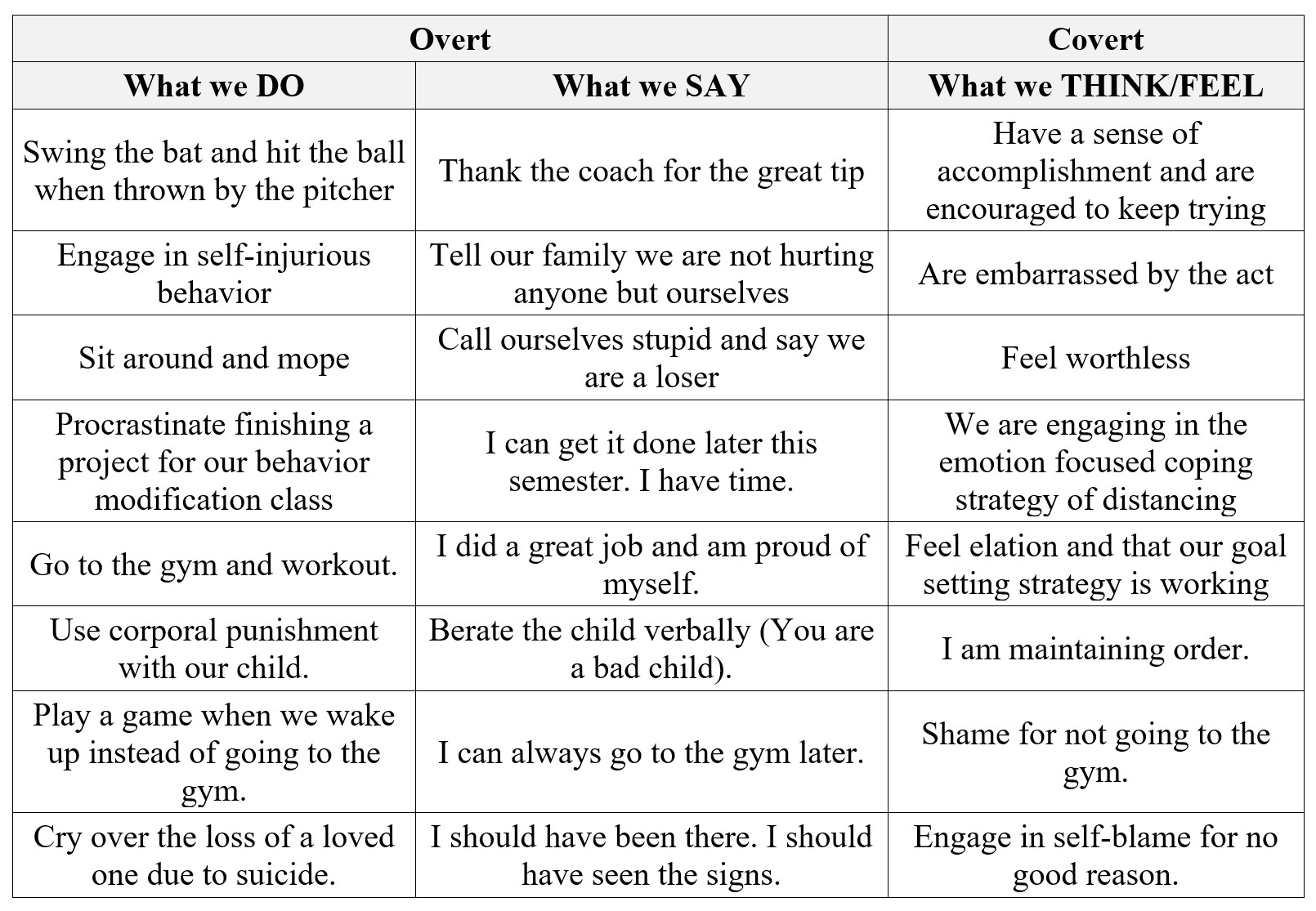

The focus of psychology is the scientific study of behavior and what causes it (mental or cognitive processes), while the focus of applied behavior analysis is changing behavior. So what forms does behavior take? Take a look at Table 1.1 for some examples.

Table 1.1. Types of Behavior People Engage In

From the table above, you can see that behavior is what people do, say, or think/feel. Behavior has several dimensions that are important to mention. They include:

For any behavior we engage in, some number of these dimensions are important. For instance, if we see ourselves as worthless (often a sign of depression), we need to figure out how long the feelings have gone on for and how intense they have become. If the thoughts (and related symptoms) occur for a short duration but are intense, this is characteristic of Major Depressive Disorder. If they last a long time (long duration) but are not very intense, this is characteristic of dysthymia or mild depression. What about running? We need to know how often we run each week, how long we run, and at what speed – the dimensions of frequency, duration, and intensity respectively. Finally, consider a father asking his son to take the trash out (as I often do with my son.) If it takes him 15 minutes to do so then this is the latency.

Behavior can be overt or covet. Overt is behavior that is observable while covert behavior cannot be observed. We might even call covert behavior private events. When a behavior is observable, it can be described, recorded, and measured. This will be important later when we talk about conducting a functional assessment in Module 5.

Behavior also impacts the environment or serves a function. If we go to the bathroom and turn on the water, we are then able to brush our teeth. If we scream at our daughter for walking into the street without looking, we could create fear in her or raise her awareness of proper street crossing procedure. In either situation, we have impacted the environment either physically as in the example of the faucet or socially as with the street incident. Here’s one more example you might relate to – your professor enters the classroom and says, “Put away your books for a pop quiz.”

Section Learning Objectives

Science has two forms – basic (or pure) and applied. Basic science is concerned with the acquisition of knowledge for the sake of the knowledge and nothing else while applied science desires to find solutions to real-world problems. In terms of the study of learning, the pure/basic science approach is covered under the experimental analysis of behavior, while the applied science approach is represented by applied behavior analysis (ABA). This course represents the latter while a course on the principles of learning would represent the former. We will discuss applied behavior analysis and behavior modification in the rest of this book.

So what is applied behavior analysis all about? Simply, we have to first undergo an analysis of the behavior in question to understand a few key pieces of information. We call these the ABCs of behavior and they include:

Let’s say that whenever Steve’s friend, John, is present he misbehaves in class by talking out of turn, getting out of his seat, and failing to complete his work. John laughs along with him and tells stories about how fun Steve is to the other kids in the 6th grade class. John is the Antecedent for the unruly Behavior, and the approval from Steve’s peers is the Consequence. Now consider for a minute that Steve is likely getting in trouble at both school and home, also a consequence, but continues making this behavior. We might say that the positive reinforcers delivered by John and his peers are stronger or more motivational for Steve than the punishment delivered by parents and teachers.

In this case, the school and parents will want to change Steve’s behavior in class as it is directly impacting his grades but also the orderliness of the classroom for the teacher. In making this plan, all parties involved will want to keep a few basic principles in mind:

If these four principles are addressed, then a sound treatment plan can be developed and implemented to bring about positive change in Steve’s behavior.

This is a great example of behavior modification at work to change the behavior of others but please note that the same principles and procedures can be implemented by an individual to bring about their own change. This is called self-management or self-modification. The final project in this course will be a self-management project and show you how to apply what you are learning to reducing an unwanted behavior or increasing some desirable one. Self-management, therefore, can be simply described as behavior modification applied to ourselves. More on this throughout the book.

Section Learning Objectives

One of the functions of science is to communicate findings. Testing hypotheses, developing sound methodology, accurately analyzing data, and drawing cogent conclusions are important, but you must tell others what you have done too. This is accomplished via joining professional societies and submitting articles to peer reviewed journals. Below are some of the societies and journals important to applied behavior analysis.

1.5.1. Professional Societies

1.5.2. Publications

Module Recap

Psychology is the scientific study of behavior and mental processes and at times our study needs to focus on how to change behavior for the better. Behavior is anything that we do, say, or think/feel and this behavior could be an excess or deficit. To determine the proper treatment strategy, we need to first figure out what triggers the behavior, or what the antecedents are, and then what maintains the behavior, or what the consequences are. Behavior modification strategies can be applied to others, but we can also apply them directly to ourselves via self-management. Once we have developed a successful treatment plan, it is important to disseminate the information to others via professional societies and peer-reviewed journals.

In the next module, we will tackle the issue of how behavior analysis and modification is scientific.